In the records of human history, the world has never been closer to complete annihilation than during the 13-day period of The Cuban Missile Crisis, a disarmingly cold name for a drama that nearly led to a catastrophic nuclear war. The Crisis unfolded in late October 1962 and pitted two of the world’s most potent superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, against each other.

It began in earnest on October 14, 1962, when American U-2 spy planes, making high-altitude passes over Cuba, captured photographic evidence of Soviet nuclear missile bases under construction. Fiery debates ignited amongst the top brass of the Kennedy administration, striving to reach a consensus on the most prudent course of action. A full-scale invasion, air strikes, diplomatic negotiations, and of course, the highly risky blockade proposition were all tabled.

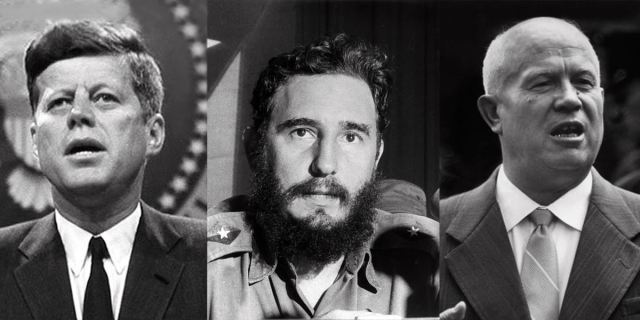

The stage for this rollercoaster of international crisis had been set a year earlier when the young and charismatic John F. Kennedy took oath as the 35th President of the United States. His administration’s early days were marred by the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion, a Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored mission to topple the communist regime of Fidel Castro. As a result, the Soviets saw this as an opportunity to extend their influence and establish a strategic foothold in the Western Hemisphere. Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Premier, agreed to place nuclear missiles in Cuba clandestinely, in an attempt to balance the strategic nuclear deterrent, which heavily favored the United States due to its Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Italy. As the nuclear stakes escalated, an intense diplomacy chess game evolved. President Kennedy sought advice from his ExComm team, a special executive committee for national security. Kennedy faced two diverging courses of action: a full-scale invasion causing potential global war or a naval blockade to halt further weaponry supplies. After much deliberation, he announced a naval blockade on Cuba on October 22nd and demanded the immediate withdrawal of Soviet missiles. Concurrently, this decision was communicated to the United Nations, rendering the crisis a global concern. Simultaneously, however, backchannel negotiations were taking place between Kennedy’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. These quiet discussions had far-reaching implications and were instrumental in breaking the deadlock.

While cool heads and careful diplomacy eventually prevailed, the world watched in trepidation as the situation continued to intensify. Kennedy’s decision to implement a naval blockade or, in the politically softened language of that day, a “quarantine”, was a key moment of escalation. The blockade was designed to prevent the arrival of more Soviet missiles, with Kennedy publicly declaring that any nuclear missile launched from Cuba would be seen as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, necessitating a full retaliatory response. The climax of the crisis loomed on October 27th, encapsulating the fragility of peace during the Cold War era. A US U2 plane was shot down over Cuba, and another strayed into Soviet airspace. Further, the USSR proposed to remove their missiles from Cuba if the United States disarmed their missiles in Turkey. Kennedy, overlooking the belligerent military advice, agreed to the demands, albeit secretly for the Turkish missile part. He also pledged not to invade Cuba. After tense negotiations, a resolution was finally reached on October 28, 1962. The Soviets agreed to dismantle their offensive weapons in Cuba and return them to the USSR in exchange for a US public declaration and agreement never to invade Cuba without direct provocation. Unbeknownst to the public, the US also agreed to dismantle their missile bases in Turkey, a factor often overlooked in this historical saga.

The Cuban Missile Crisis highlighted the very narrow line between world peace and global destruction. Although fraught with trepidation, the crisis allowed both nations to gain valuable insights into the perils of nuclear war and, more importantly, set the stage for the advent of détente, an easing of strained relations. As the most chilling chapter of Cold War history, it illustrates the critical need for patient diplomacy, open lines of communication, and, above all, the unpalatable fallout of nuclear warfare. Kennedy and Khrushchev realized the catastrophe such a war would bring, illuminating the dangers inherent in nuclear weaponry and the Cold War strategies at play. Eventually, the crisis led to a thaw in relations between the USSR and the US and brought about arms control agreements such as the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963 and the establishment of a direct communication line between the two nations.

In conclusion, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a pivotal moment in global history. It highlighted the grave perils associated with global superpowers’ brinkmanship and led to significant shifts in Cold War diplomacy and arms control. The Crisis compels us to reflect on the fragility of peace and the necessity of dialogue, understanding, and compromise in international relations. It also stands as a haunting reminder of the potential catastrophic consequences of superpower conflict, offering a poignant lesson about the enduring significance of peaceful coexistence in an increasingly interconnected world. It is an episode in human history that should neither be forgotten nor repeated, serving as a stark warning of the grim possibilities of unchecked militarism and politicized aggression.